SUN AN’ SOUL - DREAM AN’ ROME

THE HELLENISTIC ART IN THE ROMAN MUSEUMS

When we speak about the Hellenistic art we refer to the extraordinary works that came to light along the Asian coasts of the Aegean and at Alexandria in Egypt.

The main centers, where Hellenistic art developed, were Pergamon, Rhodes and precisely Alexandria.

Rome came into contact with Hellenism during the war fought against Antiochus III called the Great King,

for the vastness of his reign which extended over present-day Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, Iraq, Iran, and reached Uzbekistan as far as Afghanistan.

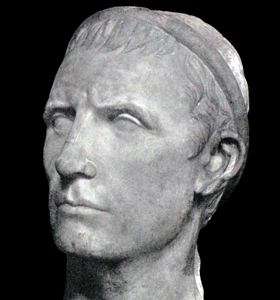

Antiochus III

With the battle of Magnesia in 190 the Romans, led by Scipio the African, defeated Antiochus and occupied Asia Minor.

In this war it was fundamental the alliance with Eumene king of Pergamum and with the Rhodes people.

|

|

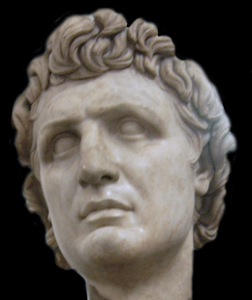

| Scipio the African |

Eumene |

The reign of Pergamo was born and developed thanks to the father of Eumene Attalo I, who was alongside the Romans in the Macedonian war against Philip V (201-197).

Philip V

Before the advent of the Romans, Attalo had to fight for the survival of his young kingdom defending it from the invasion of the Galatians, a Celtic people that starting from the Rhine and descending along the Danube, had fought against the Macedonians and Thracians, to cross around around 280 the Dardanelles strait and occupy that territory called later Galatia.

Stabilized the conquest, the Galatians attempted to reach the Aegean sea invading the kingdom of Pergamum, but were repeatedly defeated by Attalo and had to return to their lands.

Attalo

In memory of these victories of his father, Eumene raised the so-called “Donario di Attalo”, a group of five bronze statues, the work of Epigono from Pergamo, placed on a probably cylindrical base.

The statues, like most of those in bronze, given the lack of metal following the fall of the Roman empire, were fused, but fortunately the Romans had fallen in love with Hellenistic art and therefore made some replicas of the original ones.

In Rome we can see these replicas of the Donario of Attalus:

the memorable dying Galata in the Capitoline Museums,

|

|

|

|

| Dying Galata - click to enlarge |

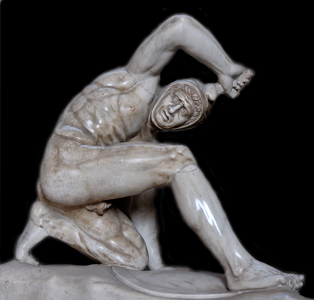

the moving suicide Galata in the Palazzo Altemps Museum

|

|

|

|

| Suicide Galata - click to enlarge |

and in the Vatican Museums the so-called wounded Persian.

Perhaps belonged to the Donario the statue of which the head has survived, even exhibited in the Vatican Museums.

|

|

| Wounded Persian |

Head |

Attalo I and his sons Eumene and Attalo II, great lovers of the arts, made Pergamus one of the most extraordinary cities of Asia Minor,

whose magnificence was shone in the altar of Pergamum, today rebuilt with original fragments in the Pergamonmuseum of Berlin.

Altar of Pergamum

With Pergamus vied Rhodes, which thanks to the skill of his admirals and his crew, could count on one of the most powerful fleets of the Aegean Sea.

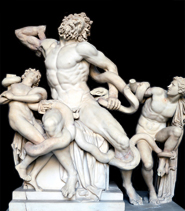

The exceptional level reached by the Rhodes artists is testified by the unforgettable Laocoonte, exhibited at the Vatican, a work attributed to Agesandro (Laocoonte), Athenodorus and Polidoro from Rhodes (his sons).

The Laocoon, found in 1506 near the Colosseum, was bought by Pope Julius II and displayed in the Vatican Belvedere courtyard and is still in the Vatican.

Obviously the bronze original has been lost.

|

|

|

|

| Laocoonte - click to enlarge |

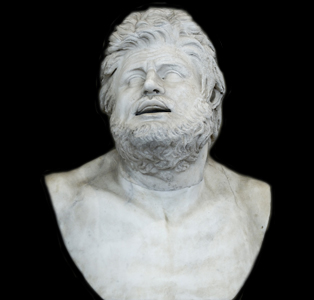

In the Capitoline Museums is exhibited the sculpture depicting the Marsia’s torture, in this case the artist who created the replica had a brilliant idea, to give back the impression of torment (according to myth, Marsia had dared to challenge Apollo at a musical contest, but the god did not take it well and had him skinned alive), he used the so-called cipollino (onion) marble, that with its purple veins makes the idea.

Indeed the Marsia Capitoline closely resembles in the facial features that of the Laocoon, so it is plausible that the original was from Agesandro or his school.

|

|

|

|

| Marsia’s torture - click to enlarge |

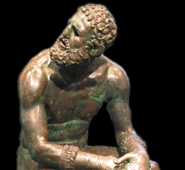

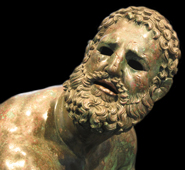

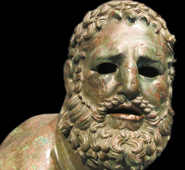

Another unforgettable example of Hellenistic art can be found in the Museo Nazionale Romano, where alongside Attalo II we see the very famous Pugilatore (boxer).

Attalo II

Each of the works we have shown you witnesses the peculiarity of Hellenistic art, as it developed over the period from 250 to 150 BC, and which represented a revolution with respect to the Athenian classicism, made memorable by the immortals Phidias, Praxiteles, Policleto, Skopas and of course Lisippo.

Classicism that exalts itself in the representation of ideal beauty, composed and transcendent.

|

|

|

|

| Pugilatore - click to enlarge |

This idealized universe is swept away by the Hellenistic art flourished during the reign of Attalus I and continued to that of the second son Attalus II Philadelphus.

And it is natural to wonder what happened in the Greek world to provoke such a revolution.

Everything had happened.

Dead the great Pericles, downed after the Peloponnese war (404) the Athenian hegemony at the hands of the Spartans, the Spartans defeated by the Tebans led by Epaminondas (362), finally destroyed the same Tebe by Alexander the Great (335), European Greece lost its independence, while the Greek cities of the Asian coast flourished, including Pergamon and Rhodes, while, founded by Alexander the Great, Alexandria was shining.

In the works we have shown you, the Hellenistic art is manifested in all its vigor, refusing the canons of the Athenian classicism, it shamelessly exhibits in the drama of the faces, in the dynamism of the representation the conquered cultural hegemony.

But it would be simplistic to give the impression that the Hellenistic world lived by only dramatization, there was also space for laughter and fun as we can appreciate in the group of the Satyr and the Ninfa (Centrale Montemartini), riconfirmed by another stalker Satiro (Palazzo Altemps),

alongside Pan who harasses Dafni (palazzo Altemps), with the excuse of teaching him to play.

|

|

|

| Group of the Satyr and the Ninfa - click to enlarge |

As far Venus she was appreciated above all squatting (National Roman Museum), as shown by a little hand.

back |